APS TOGETHER

Day 49

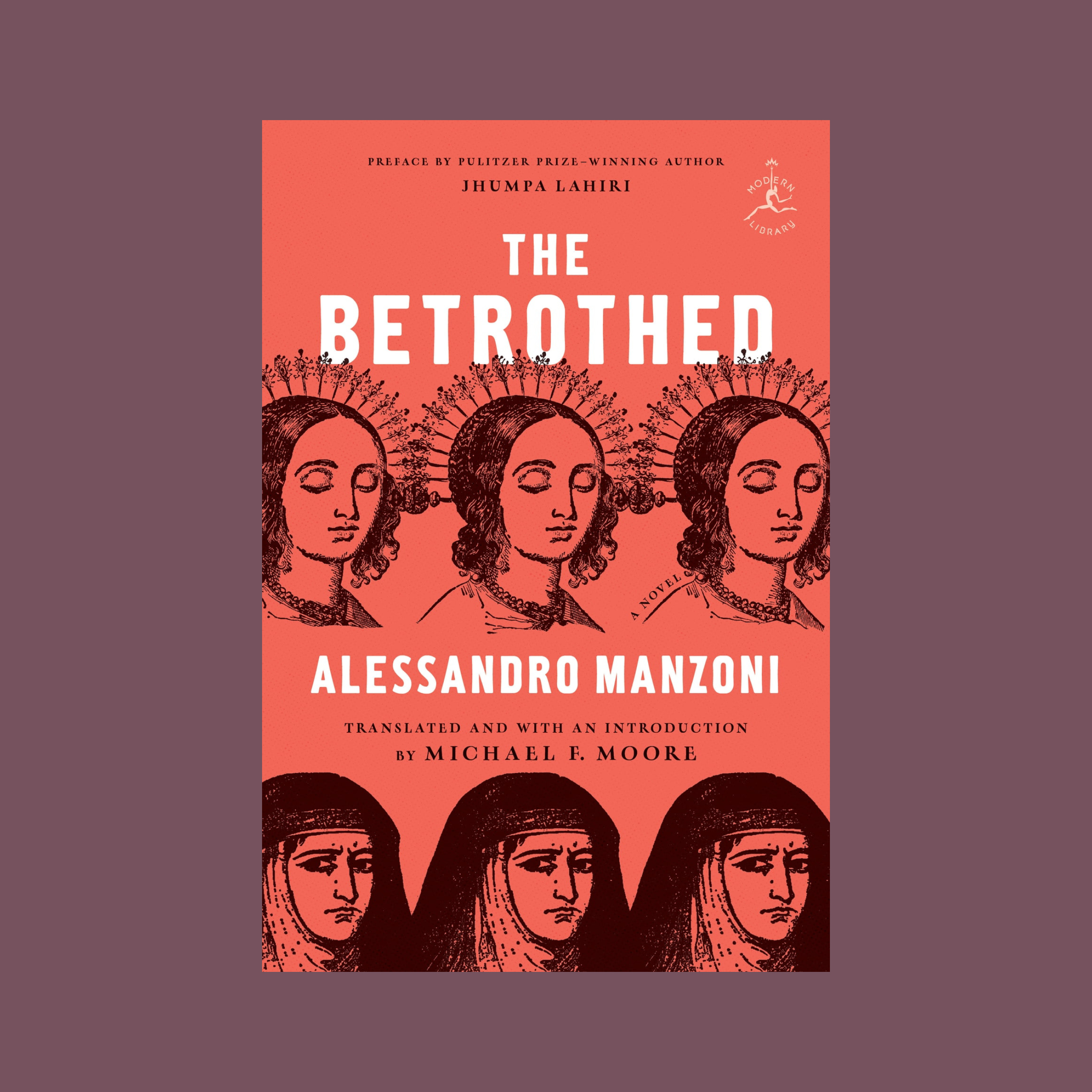

The Betrothed by Alessandro ManzoniChapter 38

April 10, 2023 by Michael F. Moore

Although I was relieved when I finally finished my translation, a cloud of melancholy descends upon me as we conclude the novel and our reading together. Manzoni also betrays his own mixed feelings in this odd little coda to his monumental epic.

Lucia is still too reserved to express her feelings. (The Italian word “pudore” does not translate easily, falling somewhere between reserve and modesty.) Until the last page:

“‘What about me? What do you think I’ve learned? I didn’t go looking for trouble: Trouble came looking for me. Unless what you mean to say,’ she added, smiling sweetly, “is that it was my mistake to love and to promise myself to you.’”

Manzoni deflates whatever expectations of Lucia we might have:

“When this Lucia appeared, there were many who thought her hair should be spun from gold, her cheeks as red as roses, each eye more beautiful than the other, and I have no idea what else. They shrugged their shoulders and turned up their noses, saying, ‘All this fuss over her?’ After so much time and so much talk, they were expecting something better. And who was she, after all? A peasant girl like many others. If that’s what you want, there are far prettier ones, ripe for the picking. Under closer scrutiny, everyone found something different that was wrong with her, and some even thought she was downright ugly.”

Not quite the Petrarchan beauty we might have imagined!

And Don Abbondio? He still refuses to perform the marriage:

“Don Abbondio was deaf in that ear. It’s not that he said no. But he continued to hem and haw, jumping from one topic to another.”

Until he hears the news that Don Rodrigo is dead.

The Marquis may be magnanimous toward Renzo and Lucia, and is certainly an improvement on Don Rodrigo, but the class divide still stands:

“I know some of you must be thinking how it would have been simpler for everyone to dine at the same table. But as I’ve explained to you, he was a good man, not an ‘eccentric,’ as he would be called nowadays. And as I’ve told you, he was a humble man, but not a paragon of humility: willing to defer to these good people, but not to spend time with them as an equal.”

Renzo is indeed a changed man, but all is not perfect. Manzoni takes a final look back at the manuscript:

“Mankind (according to our anonymous author, who you know had a strange taste in similes, but let’s quote this one, too, and may it be the last)—mankind, for as long as he is in this world, is like an invalid lying on a somewhat uncomfortable bed. All around him he sees other beds—well made, neat, and flat—and imagines that he could sleep quite comfortably in any of them. But if he does manage to change beds, as soon he settles into the new one, he’ll feel a twig pricking him here, a lump pressing him there, and find himself, in short, right back where he started. This is why—the anonymous author suggests—we should think less about feeling good and more about doing good, and thus end up feeling better.

Being a true man of the seventeenth century, his explanation is a bit laborious, but he is basically right. For that matter, he continues, our good people no longer faced troubles and tribulations of the type and severity I have recounted here. From then on, their life was the most peaceful, the most happy, and the most enviable. So much so that if I were to describe it, you would be bored to death.”

So there you have it: Manzoni thinks that happy endings are boring!