APS TOGETHER

Day 11

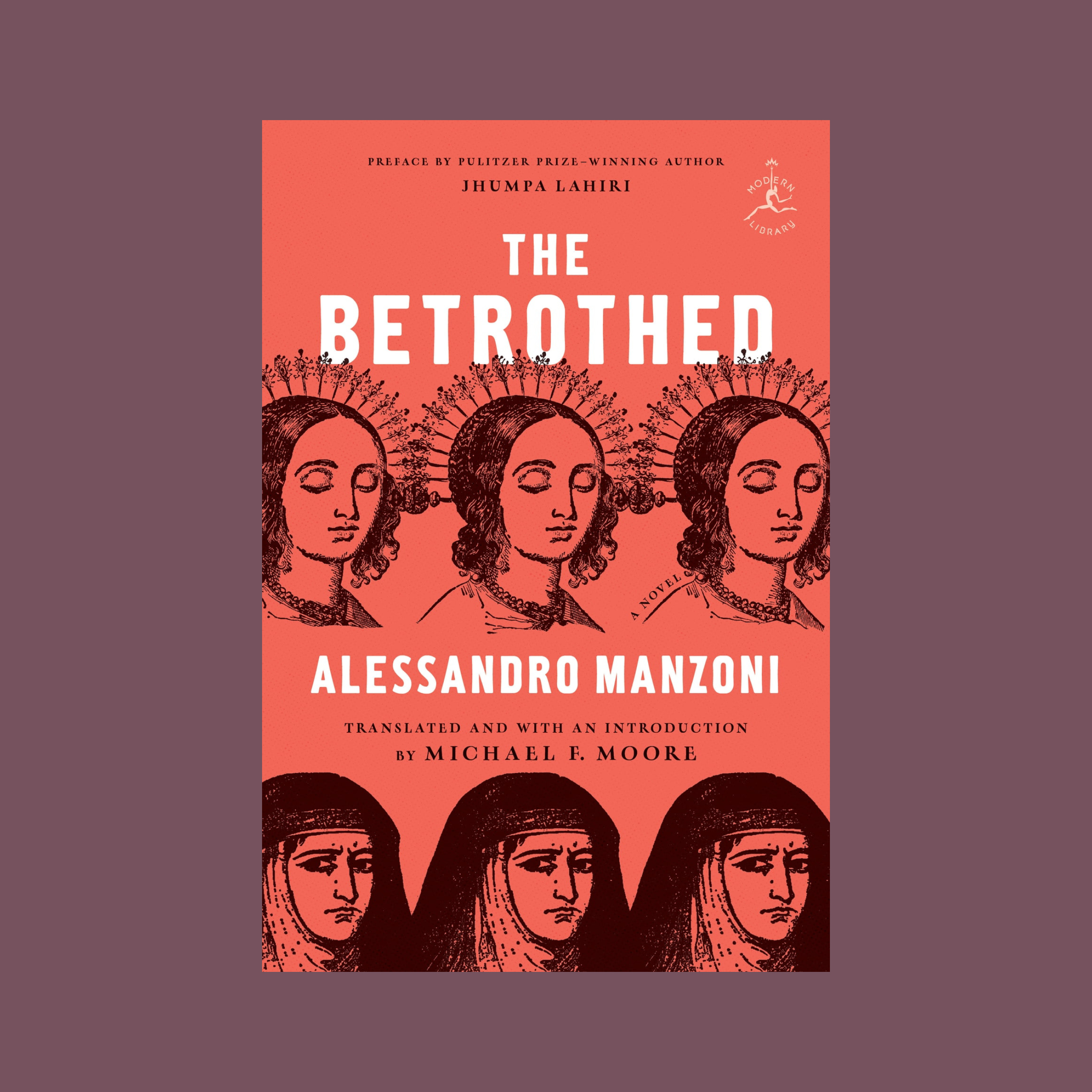

The Betrothed by Alessandro ManzoniChapter 8 (to end)

March 3, 2023 by Michael F. Moore

“Some ran, some squeezed their way through the crowd to escape. A second man arrived who had seen the bravi making their getaway, and shouted, ‘Hurry, boys, hurry! Someone’s making off with a pilgrim. Thieves or bandits. They’ve already left the village. After them! After them!’ At this announcement, without awaiting their captain’s orders, the crowd swarmed down the street. While this army advanced, some of the leaders deliberately slowed their pace, allowing the men behind them to come to the front while they themselves disappeared into the rear. The motley crew finally reached its destination.”

One of the first instances of Manzoni describing a crowd scene. Not even Dickens captured the chaotic energy of the mob so effectively. This is also one of the first appearances in the novel of the word “confuso” and its variants (confusa, confusi, confusion): I counted 129 instances of them in the novel, and had to handle each in a different way. The motley crew is a “sciame confuso,” confused swarm, but I chose to gift the verb “swarm” to the earlier sentence, and use this more common and comical expression.

Some rules are meant to be bent!

“At that the sacristan could no longer contain himself. Taking the padre aside, he whispered in his ear, ‘But, Padre, Padre! At night… in the church… with women… closing… the rules… but, Padre!’ and he shook his head. As he listened to the man struggling to get the words out, Padre Cristoforo thought, ‘Will you look at this. Had it been a fugitive from justice, Fra Fazio wouldn’t have given it a second thought. But a poor innocent girl, escaping from the clutches of a wolf… ’ ‘Omnia munda mundis,’ he said, suddenly turning toward Fra Fazio, forgetting that the man did not understand Latin.”

Padre Cristoforo does not deliberately use Latin to bully the other man, unlike Don Abbondio in his first confrontation with Renzo. Literacy and illiteracy, in either Latin or Italian, as what we might call a status symbol, underlies the entire novel, written, as I mention in the introduction, in part to modernize Italian and bring the written language closer to the spoken.

Page 140. “Farewell mountains…” This passage concludes the first part of the novel.

When I presented the book at the NYU Casa Italiana in October, I had this passage read by an actor friend, Demosthenes Chrysan. His voice broke in the middle, at the image of a village left behind, of a migrant forced to leave his homeland. When I read it myself at a public presentation a week later, the same happened to me. Which leads me to think of how in translating, we have to mix the cerebral and the emotional, the Apollonian and the Dionysian: the rational ability of the mind to find semantic equivalences, and the sentimental capacity of the heart to feel and express the emotions being conveyed.

The latest TV adaptation, with a score by Ennio Morricone, mixes the male and female voices in an interesting way.