APS TOGETHER

Day 15

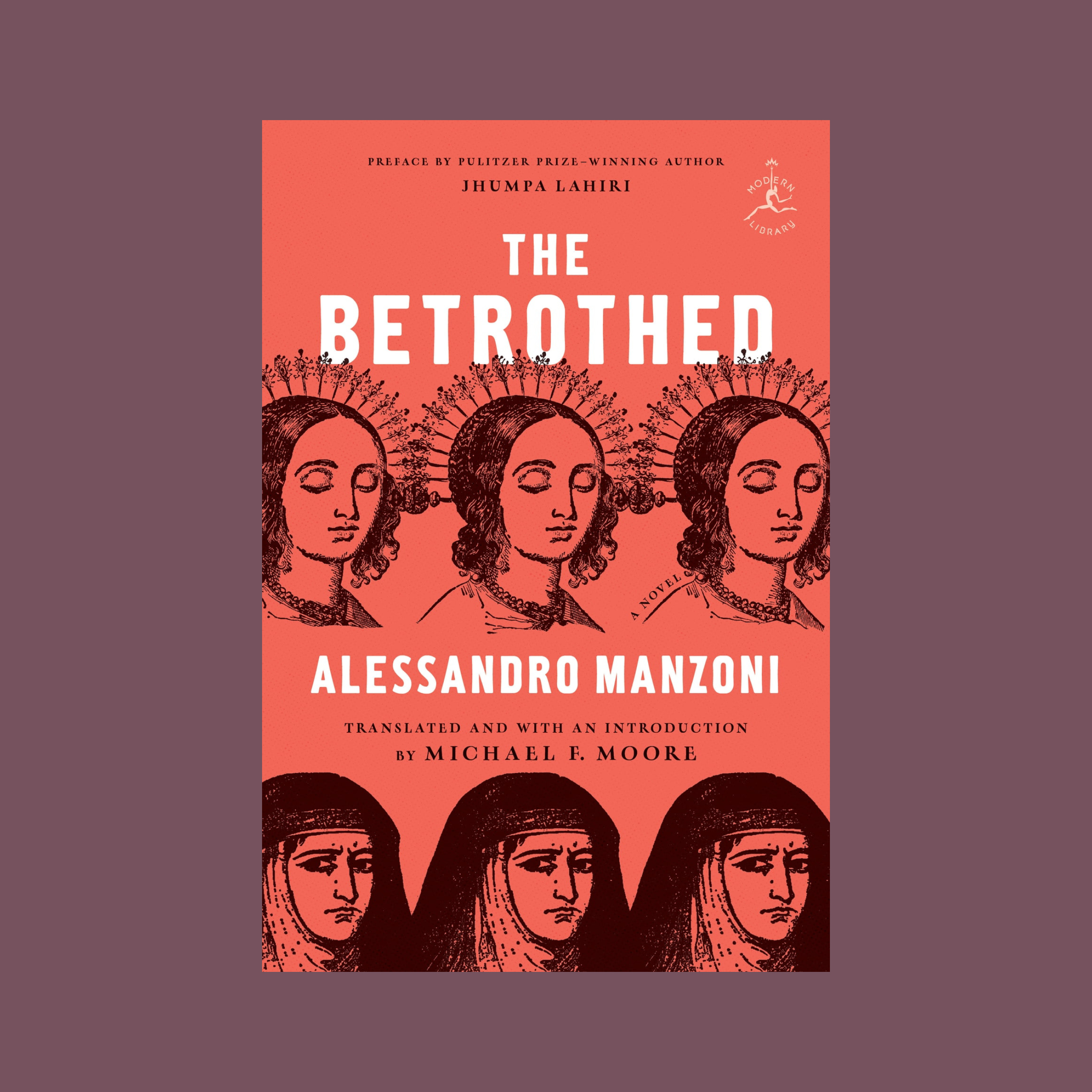

The Betrothed by Alessandro ManzoniChapter 10 (to end)

March 7, 2023 by Michael F. Moore

“The true answer to that question leapt to Gertrude’s mind with a terrifying clarity. To give that answer, she would have to explain what had happened, say who had threatened her, tell the story… The unhappy girl shrank from this idea in fear. She hastened to find another answer, and found only one, the one farthest from the truth, which would free her from that torment swiftly and surely. ‘I am becoming a nun,’ she said, hiding her agitation, ‘I am becoming a nun of my own free will.’”

Gertrude discovers that it is easier to tell someone what they want to hear—to lie—than to relate the messy truth.

“And she gave her fateful reply.” Virtually every Italian knows this passage by heart: “La sventurata rispose,” and I am often asked how I translated it. In the earlier draft of the novel, Fermo e Lucia, this sentence is followed by a detailed account of the Signora’s descent into sin. Juicy reading, and the reason some Italians prefer this previous version. Manzoni’s decision to excise it persuades me, instead, that his story-telling instincts were on point. He sets our imaginations to work and lends the plot a bit of a cliff-hanger. But he also creates a dilemma, for in this moment his (and our own) compassion for the young girl should mutate to abhorrence at the actions of the adult woman.

So why did I translate it this way? Earlier translations rendered “sventurata” as wretch, which got me humming “Amazing Grace.” Italian has a way of turning adjectives into nouns that can sound pretty awkward if translated literally or, as is often done, following the adjective with “one.” A “sventura” is a moment of bad or adverse luck, a misfortune. But hanging over the Italian word is the notion of fate, of an unseen force determining the bad luck that has befallen you. So I took the word “fate,” shifted it to modify the noun “reply,” and after wavering between “fated” (controlled by fate) and “fateful” (a quality of ominous prophecy), I came up with “And gave her fateful reply.” I also just like the way it sounds.

Some critics have called these excursions “digressions.” I disagree. The novel embeds a series of stories within the larger plot that lend it variety and sparkle. Now that we have heard the nun’s story, Manzoni brings us back to the narrative present, and the prying questions about sex that La Signora is asking of Lucia. Once again, Agnese steps in with a little homespun wisdom:

“‘Don’t be surprised,’ she said. ‘When you know the world as well as I do, you’ll see that there’s nothing to be surprised at. Nobles are all a little bit mad: some more, some less, some in one way, some in another. It’s best to just let them talk, especially when you need them. Pretend that you’re taking them seriously, as if they were saying reasonable things.’”

Will someone please write a novel about Agnese?