APS TOGETHER

Day 24

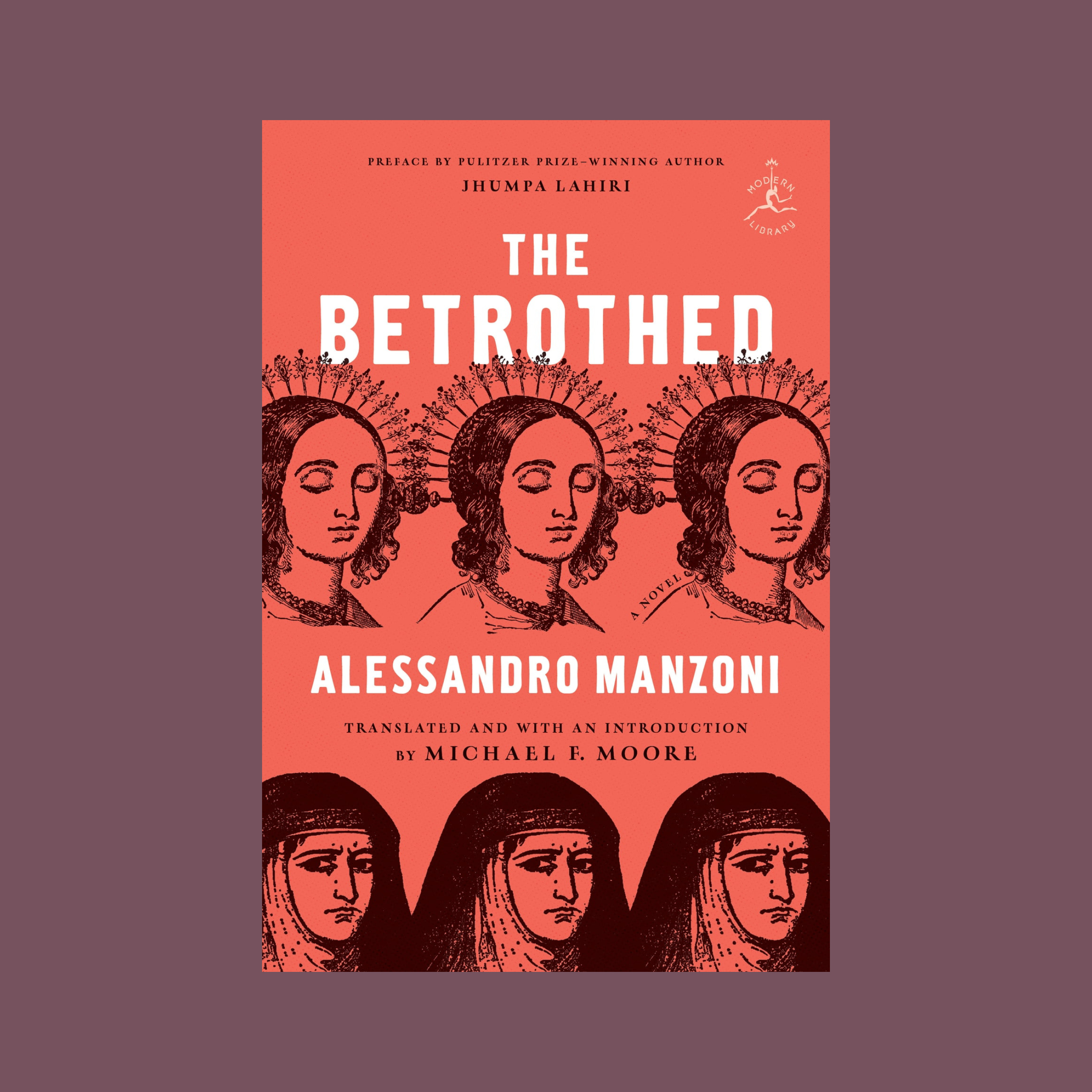

The Betrothed by Alessandro ManzoniChapter 18

March 16, 2023 by Michael F. Moore

Back to Pescarenico and the rumor mill. We the readers know exactly what Renzo did, but the people of the village are hearing only official reports that they know in their hearts to be untrue:

“The rumor circulated that he had done something terrible, but either no one could say exactly what it was, or they gave a hundred different versions. The worse it was purported to be, the less it was believed by the people in the village, who knew Renzo to be a good boy.”

Their suspicions, naturally, fall on Don Rodrigo:

“‘The road to iniquity,’ says the manuscript at this point, ‘is wide but that does not mean it is easy. There are many bumps and rough patches along the way, and though the road goes downhill, it is arduous and tiring.’”

Meanwhile, back at the convent in Monza:

“She also warded off, as best she could, the nun’s prying questions about her life before her engagement. This was not out of caution, but rather because it was a story more agonizing, more difficult to tell than all the ones she’d heard from the Signora (and even the ones still to come). The nun’s stories were filled with cruelty, scheming, and suffering: things that were awful and painful but could still be named. Lucia’s stories, by contrast, contained a sentiment, a word that she didn’t feel she could utter when speaking about herself. A word she could never paraphrase in a way that didn’t seem too bold: The word was love!”

LOVE!

Manzoni, too, is reluctant to utter the word. I believe this is the only instance in the novel—the romantic genre par excellence—in which the word “love” is used in the romantic sense.

Where has Padre Cristoforo disappeared to? Enter the Conte Zio, the powerful Count Uncle:

Manzoni skewers his prestige by relating the man’s account of his trip to the Imperial Court in Madrid:

“You should have heard him describe the welcome he had received there. Suffice it to say that the Count-Duke of Olivares had treated him with special regard and taken him into his confidence, as shown, for example, by having once asked him—in the presence, you could say, of half the court—how well he liked Madrid, and, another time in the bay of a window, he told him that the Duomo of Milan was the largest church in His Majesty’s domains.”

The Count’s farewell words to his nephew:

“Don’t do anything stupid!”

Short loaded sentences are often harder to translate than long elaborate ones. The Italian, “E abbiamo giudizio,” uses the first-person plural (“abbiamo” = we have) the way a nurse might ask, “How are we doing today.” “Giudizio” is a word that recurs in the novel, but not so much in the legal sense (in a novel that denounces injustice). According to the online Treccani dictionary, the familiar meaning is “senno, riflessione, prudenza”—sense, reflection, prudence. Manzoni famously makes a distinction between “good sense” and “common sense,” but more on that later. “Reflection” doesn’t quite fit into a sentence. We could say, “Be prudent,” which sounds a bit prudish in the mouth of the Count Uncle or the ear of Attilio. “Be smart”? “Act wisely?” A bit too upper crust. Although many think of Italian as a romantic language, it actually has more synonyms for “stupid” than for “love.” (Ask me sometime and I’ll give you a few). The true sentiment behind these words is best expressed by Ru Paul, in her command to the two contestants about to lip-sync for their life.

Tempting, and a perfect example of dynamic equivalence in translation, but no. Rather than write the affirmative, “Be smart,” I opted for the negative, “Don’t do anything stupid.”