APS TOGETHER

Day 7

The End and the Beginning. Pages 281-316.

August 12, 2020 by Ilya Kaminsky

I love overhearing the echoes in Szymborska’s poems. See for instance, the ending of “Some People Like Poetry”:

"Poetry—

but what is poetry anyway?

More than one rickety answer

has tumbled since that question first was raised.

But I just keep on not knowing, and I cling to that

like a redemptive handrail."

Compare it to the final lines from “A Note,” written decades later:

“and to keep on not knowing

something important.”

The lines “to be a dog, / or stroke its warm fur; / to tell pain / from everything it’s not; / to squeeze inside events” remind me of one of Szymborska’s collages

“But I just keep on not knowing, and I cling to that / like a redemptive handrail.” The question of not knowing is quite present in her work. In the same book, we find “Elegiac Calculation”

“How many of those I knew

(if I really knew them),

men, women

(if the distinction still holds)

have crossed that threshold

(if it is a threshold)

passed over that bridge

(if you can call it a bridge)”

“Maybe all this / is happening in some lab?” she asks. What is it, this strange world to which we are so entangled? To which we owe everything?

“Every tissue in us lies

on the debit side.

Not a tentacle or tendril

is for keeps […]

I can’t remember

Where, when, and why

I let someone open

this account in my name.

We call the protest against this

the soul.

And it’s the only item

not included on the list.”

“We call the protest against this / the soul”: what I love about Szymborska’s poetry is that the warmth of the soul pops up in most unpredictable places. She refuses to die, yes. But does so without bluntness. Her language is a sense of humor.

She refuses to die because dying would be bad for her cat. Here are some lines from "Cat in an Empty Apartment"

“Die—you can’t do that to a cat.

Since what can a cat do

in an empty apartment?

Climb the walls?

Rub against the furniture?”

I love how this poem takes on a cat’s point of view: “Nothing has been moved, / but there is more space”

The reader realizes this is a poem at the edge of the abyss:

“Someone was always, always here,

then suddenly disappeared

and stubbornly stays disappeared.”

And, yet there is humor:

“Just wait till he turns up,

just let him show his face.

Will he ever get a lesson

on what not to do to a cat.”

Szymborska hits us with grim realization, with laughter, with empathy, and then with the sober fact of death: no second chances.

We the readers have this unspoken realization even as the cat plots the actions that will never take place:

“Sidle toward him

as if unwilling

and ever so slow

on visibly offended paws,

and no leaps or squeals at least to start.”

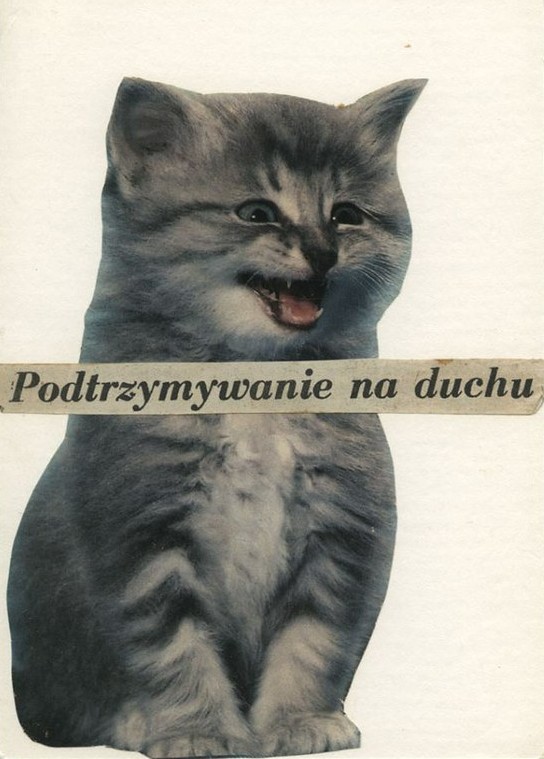

And, here is a cat Szymborska wanted you to see in one of her collages:

Protest against the mechanization of our life is the soul. After every crisis, instead of numbness, comes “cleaning up.”

“Someone has to shove

the rubble to the roadsides

so the carts loaded with corpses

can get by.

Someone, broom in hand,

still remembers how it was.

Someone else listens, nodding

his unshuttered head […]

Someone has to lie there

in the grass that covers up

the causes and effects

with a cornstalk in his teeth,

gawking at clouds.”

“The little soul,” Szymborska says in her great poem “Torture,” recalling Hadrian’s famous, ages-old piece. Here it is in W. S. Merwin’s translation of Hadrian’s “Little Soul”

“Little soul little stray

little drifter

now where will you stay

all pale and all alone

after the way

you used to make fun of things”

Earlier, I said that Szymborska is a poet who finds herself in the midst of life. What did I mean by that?

I meant: she is someone who writes with equal relish about a bodybuilder’s contest (“From scalp to sole, all muscles in slow motion / The ocean of his torso drips with lotion”) and on Heidegger’s concept of Nothingness.

I meant: she is a poet who, even in her bleaker moments, finds a surprise, awe, astonishment even, at the strange fact of our being here at all.

I meant: in her first book published after the fall of the Berlin Wall, she attests that “reality demands / that we also mention this: / life goes on.”

And so on p. 290, she gives us a tour of famous slaughter grounds of history, from Borodino to Hiroshima. Guess what? It turns out they are a place like any other. Gas stations. Ice cream parlors.

“Perhaps all fields are battlefields,” she says, “those we remember / and those that are forgotten.”

It is a sobering (and also somewhat surprising) perspective for a Polish poet, given that country’s traumatic history. What is the demand of reality here?

That we take into account how—despite all the crisis—the world mysteriously renews itself.

“On tragic mountain passes

the wind rips hats from unwitting heads

and we can’t help

laughing at that.”