APS TOGETHER

Day 6

The People on the Bridge. Pages 237-276.

August 11, 2020 by Ilya Kaminsky

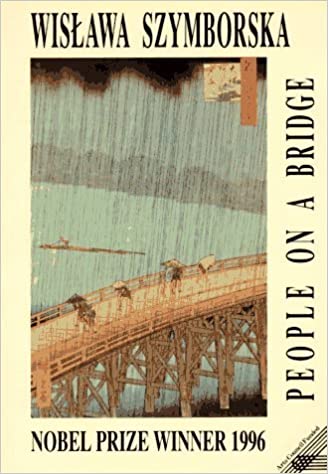

Ten years pass. In her next book, People on a Bridge, Szymborska continues to explore our collective strangeness.

Let’s try a different translation for a moment. Look at Adam Czerniawski’s translation of “People on a Bridge,” which you can compare to the version in MAP.

Joanna Trzeciak notes “People on a Bridge” alludes to a woodblock print titled Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). Szymborska found the inspiration for the poem in a postcard received from a friend.

“This isn’t by any means an innocent picture. / Here time has been stopped” she writes. Time and its strangeness appear quite a bit in Szymborska’s writing. We mark time to mark our imperfections.

It is time that we see lurking behind the avalanche of jackets, blouses, suits, and handbags in “Clothes.” It is time that we overhear in “View with a Grain of Sand.”

“A second passes.

A second second.

A third.

But they’re three seconds only for us.

Time has passed like a courier with urgent news.

But that’s just our simile.

The character is invented, his haste is make-believe,

his news inhuman.”

Speaking of time: here is a little collage from Szymborska. Drown your sadness in wine, the proverb goes. Is that what she suggests, that time is our sadness?

How naïve we are, trying to see through time: “Hitler’s First Photograph” mocks the present for its ignorance of the future.

And who’s this little fellow in his itty-bitty robe?

That’s tiny baby Adolf, the Hitlers’ little boy!

Will he grow up to be an LLD?

Or a tenor in Vienna’s Opera House?

Whose teensy hand is this, whose little ear and eye and nose?

Whose tummy full of milk, we just don’t know:

Printer’s, doctor’s, merchant’s, priest’s?

Where will those tootsy-wootsies finally wander?

To a garden, to a school, to an office, to a bride?

Clare Cavanagh: It is a shockingly inappropriate opening for the twentieth century’s most infamous biography: could Hitler have ever been an infant? “Where will those tootsy-wootsies finally wander?” the speaker asks, and the question would have been genuinely open back in 1889, unimaginable as that is in hindsight: in Braunau, “a small, but worthy town…no one hears howling dogs, or fate’s footsteps.”

Beware of the ways we tell tales, Szymborska warns.

I am thinking of Hamlet here. Soon after the play begins, the reader knows there won’t be any happy ending. Yet, it is the delaying of the horror via poetry, what keeps us hooked. Note all the details in this poem, note the role these details play. Note the subtext. Wonderful to see how first lines in Szymborska’s poems work: often she begins with an assertion, almost a thesis statement. She makes a proposition (“my sister doesn’t write poems” or “nothing can ever happen twice” or “we are children of our age, / it is a political age” etc.) and then looks at it from a myriad of perspectives, pushing that ticket as far as it can go.

She will go on exploring this assertion throughout “Children of Our Age,” and then she will tersely undercut it at the end:

Meanwhile, people perished,

animals died,

houses burned,

and the fields ran wild

just as in times immemorial

and less political.

Lots of question marks in her poems. Question marks might be Szymborska’s favorite piece of punctuation. She is the kind of a poet for whom existential angst means one must keep asking questions. (In her Nobel lecture she asserts you cannot be a poet without admitting: I do not know.) Yet, where another writer might despair at human ignorance, at all the unknowing, at questions—Szymborska finds this to be a reason for amazement.

By now the attentive reader knows: from her skepticism comes not despair, but a kind of joy. (This becomes more and more apparent as we keep reading into her final books.)