APS TOGETHER

Day 3

No End of Fun. Pages 109-150.

August 8, 2020 by Ilya Kaminsky

Writing about Szymborska’s poems, Edward Hirsch asserts that her lines “take place on the edge of an abyss. It’s the poetry of the close shave. It’s not only accidents we contend with, but history itself, with its hatreds and more deaths than we can count. Against which: the imagination, the joy of writing.”

Hirsch: The title “The Joy of Writing” points not to the art of poetry, but to the joy—the jouissance—of writing, the deep pleasure of the activity itself. The poem alertly raises some basic questions about… the relationship between words and things.

Hirsch: This is not a rhetorical question but a genuine problem which the poem sets out to investigate. It suggests that the poem is not a set up, a construct thought up wholly in advance, but an ongoing process of listening and making. Why does thisimaginary doe, as soon as it is inscribed, seem to take on a life of movement through an equally imaginary woods? And where is it going?

“Why does this written doe bound through these written woods?”

But then, the poet asserts her control. Note the fourth stanza:

“Not a thing will ever happen unless I say so

Without my blessing, not a leaf will fall,

Not a blade of grass will bend beneath that little hoof’s full stop.”

The poem as a shield against death. That is what the joy of writing consists of for Szymborska:

“The joy of writing.

The power of preserving.

Revenge of a mortal hand.”

Szymborska: “I prefer the absurdity of writing poems/ to the absurdity of not writing poems."

O how these lines from “Landscape” will echo ten years later in her poem “Lot’s Wife”!

“Even if you called I wouldn’t hear you,

and even if I heard I wouldn’t turn,

and even if I made that impossible gesture

your face would seem a stranger’s face to me.”

A useful observation: Joanna Trzeciak notes that“Landscape” has similar images to Milosz’s piece “Dining Room,” the fourth poem in his 1943 cycle “The World."

Echoes.

“My soul is as plain as the stone of a plum”—as we keep discussing the evolution of love poems in Szymborska, this poem offers quite a few sober lines on the subject. As does “Laughter."

“That little girl I was— / I know her, of course”: as I read “Laughter” I can’t help but think of Shklovsky’s idea of uses of ostranenie (estrangement) in literature.

I also sense that use of ostranenie in the next poem, “The Railroad Station”: “My absence joined the throng / as it made its way toward the exit.”

I am drawn to the uses of negation in “The RailroadStation.” It’s magnetic.

“While they kissed

with not our lips,

a suitcase disappeared,

not mine.

The railroad station in the city of N.

passed its exam

in objective existence

with flying colors.”

In a way repetition and imagery make the nearly bureaucratic language emote:

“Somewhere else.

Somewhere else.

How these little words ring.”

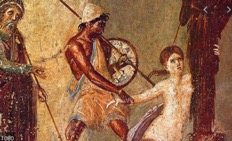

Is it just me, or almost every poem here is an ars poetica? Take, for example “Soliloquy for Cassandra.” Cassandra speaks about her ignorant countrymen here, but of course it is also the poet speaking about us, her readers:

“I loved them.

But I loved them haughtily.

From heights beyond life.

From the future. Where it’s always empty

and nothing is easier than seeing death.

I’m sorry my voice was hard.Look down on yourselves from the stars, I cried”

To my mind, “Soliloquy for Cassandra” is one of the keys to Szymborska. I’ve heard critics complain, at times, that this poet’s “distant, cold.” This piece addresses the complaint, yes. And, while at it, we also get some serious heartbreak:

It turns out I was right.

But nothing has come of it.

And this is my robe, slightly singed.

And this is my prophet’s junk.

And this is my twisted face.

A face that didn’t know it could be beautiful.

Even in the “prophetic” poems, such as “Soliloquy for Cassandra,” Szymborska still refuses the poetic “pose”: the robe is singed, but“slightly.” Cassandra might be a prophet, but cares little for “prophet’s junk.”

What is the last word? “Beautiful”: the face of Cassandra is beautiful. Though it didn’t know it could be so.

But I said “Soliloquy for Cassandra” is ars poetica. Why? Because of this line:

“Look down on yourselves from the stars, I cried.”

As you read through Szymborska’s work you realize very quickly that she is a master of perspective. She looks at humans as if from the perspective of the moon. She reports about humans to stars, to snowmen.

To see your strangeness: “look down on yourselves from the stars”

Let’s consider this perspective. After all, many great writers do take this perspective of estrangement. I already mentioned Shklovsky. I could have mentioned Chekhov, too. Here is Sebald on Nabokov:

Nabokov’s main narrative technique is to introduce, through barely perceptible nuances and shifts of perspective, an invisible observer—an observer who seems to have a better view not only than the characters in the narrative but than the narrator and the author who guides the narrator’s pen. It is a trick that allows Nabokov to see the world, and himself in it, from above. In fact, his work contains many passages written from a kind of bird’s eye view.From a vantage point high above the road, an old woman picking herbs sees two cyclists approaching a bend from different directions. From even higher up, from dusty blue of the sky, an aircraft pilot sees the whole course of the road and two villages lying twelve miles apart. And if we could mount even farther up, where the air grows thinner and thinner, we might perhaps, says the narrator, at this point see the entire length of the mountain range and a distant city in another land—Berlin, for instance. This is to see the world through the eye of the crane. […] Writing, as Nabokov practiced it, is raised on high by the hope that, given sufficient concentration, the landscapes of time that have already sunk below the horizon can be seen once again in a synoptic view.

Did Szymborska learn this perspective from someone like Nabokov or Shklovsky? Not necessarily. There are many other examples. She has a little essay, “Nervousness,” citing Milosz’s importance for her work. Milosz has a series of poems, “The World,”where he explores just this kind of perspective. A number of scholars drew parallels between that poem of his and Szymborska’s later work. (Some scholars also drew parallels between Szymborska and another polish poet, Tadeusz Różewicz.)

Where did Milosz get it? Many would say William Blake.Perhaps. But I think he got it from the marvelous children’s writer Selma Lagerlöf, about whose book, Wonderful Adventures of Nils, he wrote:

“A book I loved [as a child] places a hero in a double role.He is one who flies above the earth and looks at it from above but at the same time sees it in every detail. This double vision may be a metaphor of the poet’s vocation.”

“Distance is the soul of beauty.”

—Simone Weil

“Look down on yourselves from the stars, I cried.”

—Wislawa Szymborska

I hope you will go ahead and look at another poem, “Pietà.” Here is some interesting information about it from Magnus J. Krunski and Robert A Maguire who say that this poem is “set in Bulgaria, which Szymborska visited in 1955. The heroine is the woman known through the Soviet Bloc in the 1950s as “Mother Vaptsarova.” Her son Nikola Vaptsarov… was a common laborer and a well-known poet. For his activities as an underground fighter during WWII, he was executed by the pro-Nazi regime (July, 1942). Vaptsarova lived in a hut… [and it] had become de rigueur for political and literary celebrities to visit her during trips to Bulgaria… {Szymborska} did not publish this particular poem until 1967. Conditions being what they were in Poland in the 1950s, it would have been impossible to show Vaptsarova as a victim of the media, and to treat her with such sympathetic irony.”

As you read the next few pages you will see that in fact there are two very different poems about mothers, published around the same time, both quite heartbreaking. The second piece is “Vietnam.”