News

Reviving Maria d’Arezzo, Presidentessa Dada

April 23, 2015 by Olivia E. Sears

Translation may be the invisible art, but the translator's mission is precisely to bring visibility to a work of literature, and at times to rescue an author from obscurity. This is especially true when translating Italian women writers of the past who struggled for visibility even within their own culture.

In a recent interview, Elena Ferrante, the renowned (though anonymous) contemporary author of a series of novels about Naples, has said that she writes under a pseudonym so that the focus of attention will remain on her books—in which she writes intimately about women's lives—and not on "some writer-hero.” While she has attained remarkable prominence in a short time, her work revolves around women who struggle to find their place in society. And yet in the Italian press there has been a persistent rumor that Elena Ferrante is in fact the pseudonym of a successful male novelist, perpetuating the search for the writer-hero, presumed to be male.

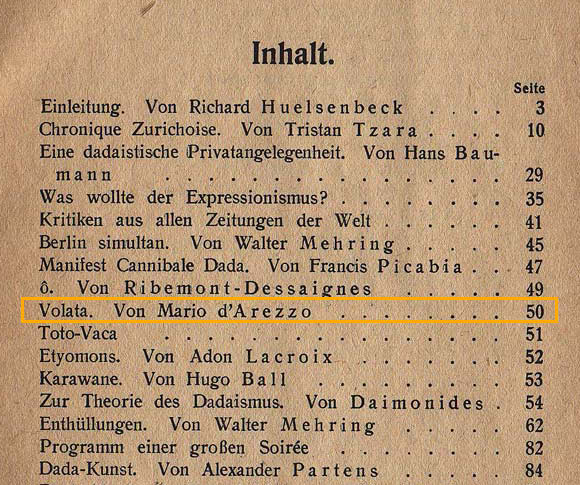

Maria d'Arezzo, an Italian woman writer who lived and wrote in Naples a hundred years ago, also chose to write under a pseudonym (though her motivations for doing so are lost to history). In 1917, Dada founder and poet Tristan Tzara traveled to Naples to recruit this poet, little known outside Italy, to his movement. Despite d'Arezzo's assertions of creative independence, Tzara conferred on her the title of Presidentessa Dada in Paris and presented her poem “Volata” ("Flight") at his Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. The Dada movement included numerous women (and présidentes), but when d'Arezzo made her international debut in the pages of the legendary Dada Almanach (Berlin, 1920)—the volume that collected the works of Tzara and his circle—her poem ultimately proved to be the only work by a woman to appear in the anthology.

In the table of contents, however, the poet was listed as Mario d'Arezzo—an error perpetuated to this day on the official Dada Companion website. So here's to reviving Maria, who boldly declares in her poem "Andante":

Tonight I am everything and I am made of nothing—

I have even forgotten my name—

Born Maria Cardini in 1890, she published her debut volume of poetry in 1913 (under her given name) but soon thereafter confessed that she no longer recognized herself in its fairly conventional style. Adopting her nom de plume (Arezzo being the city of her birth), she began to ally herself with the avant-garde journals of the time, serving as editor of Le pagine, and in 1918 published Scia [Wake], a book closer in spirit to the Dada avant-garde, with flashes of near-Futurist dynamism, unusual metaphors, synesthesia, and occasional syntactical experimentation.

And yet, within the span of a few short years, by the age of thirty, she had completely abandoned creative writing and dedicated herself to translation. Her entire poetic career had flown by in a kind of fevered sprint—what in Italian is referred to as a volata, the kind of thing that leaves a wake (scia).

As it happens, movement (or stagnation) and escape (or confinement) were d'Arezzo's major poetic concerns, and her work is imbued with a spirit of restlessness. The titles of the two poems from Scia translated in APS 22—"Andante" (1916) and "Volata" (1917)—are words of movement also used in music. Andante—from the verb andare, to go or walk—is used as an adjective in Italian to mean affable (for people), cheap (for quality), or simple (for style)—all with a generally easygoing connotation. But outside of Italy, andante had long ago been adopted in music as a tempo marking—defined as a walking pace—so a listener seeing a musical movement labeled andante would expect to hear music that is neither too fast nor too slow. Instead, d'Arezzo immediately follows her title with the startling opening statement: "I would not be surprised to find I am dead." She continues:

I feel so distant so dead so at peace

while the hours slide by, silent...

She interprets this steady sliding pace as a "ritmo d'immobilita," a rhythm of stillness or immobility. By contrast, the title of the second poem, "Volata" (from volare, to fly), conveys speed. In its original meaning, volata refers to a flock of birds in flight, but it is commonly used to describe a sprint or a rush. Volata is also a term used in music—a fast run of notes—but not widely, and generally not outside of Italy. Hence, in the translation, "andante" had to stay and "volata" had to go. The poem "Flight" incorporates a number of phrases from languages other than Italian, and in the translation I largely preserved the kaleidoscope, as it is native to much avant-garde poetry of the time. Most of the phrases from French and German—which serve mostly for style and sound, as part of the whirlwind of the poem—would be familiar enough to readers.

The only non-Italian phrase I translated was "bleu cendre" because the ashen blue is an important detail in itself, contrasting the narrator with the statue of the Madonna. The narrator's blue tunic is ample like the open sky in contrast to the small, rigid image of the Madonna—who always appears dressed in blue in Italian iconography, and is inextricably associated with the color—stuck in the hard vault of her "heaven." In "Flight," d'Arezzo sets up the opposition of free flight versus a fixed ideal, a ceramic beauty, embedded in the "duro cielo" (hard sky) of the ceiling. She imagines herself rising out of a preordained destiny to soar up, alive and growing, like a rose. And yet the rose is fragile ("sottile"); the statue is secure in its place, while the rose must try to find its bearings. D'Arezzo is explicitly writing about the conflict faced by a woman, but by invoking flight—a particular obsession among Italian Futurist poets of the time, who idolized machines and symbols of freedom—she engages in the larger poetic conversation. A well-known 1915 poem by Ardengo Soffici, a panegyric to the airplane and the rapture of flight ("Aeroplano"), names dozens of colors of blue in its ecstatic description of the "firmament" and describes the largest stars as roses. D'Arezzo's poem might well have been a response to this and the many other contemporary paeans to flight, with her own unique twist.

Rather than the prevalent yearning to fly, D'Arezzo articulates a more specific desire: to flee. In “Flight,” she grapples with the longstanding dichotomy endemic to the Italian view of women: one is either "Madonna" (virgin, mother—or, better yet, virgin mother) or "whore." However, here the confinement of the little ceramic statue of the Madonna (a "madonnina," the diminutive) is contrasted not with the fate of a fallen and failed woman but rather with one who will fly free:

I have wings—

but I could also set myself like a little white madonna in that hard

sky of blue tile shining above—

The ceiling is a hard sky where the statue perches even higher than a pedestal, and where it is mounted, immobile. (A side note here about the verb "incastonare": normally used for tile and gems that are mounted, set, or encrusted, d'Arezzo makes the verb reflexive, which limits one's choices in English. I had to reject "I could mount myself there.")

Numerous poems throughout Scia revolve around the theme of escape. In “Certain Domestic Evenings,” the narrator depicts herself “with the soul of a predator in a sparrow's nest ... coming home to the order of life with a soul in rebellion—and sitting down calmly when we really want to dance strangle smash.” (The shift to the first person plural might be read as a statement about how common this feeling is among bourgeois women of the time.) In "Unmoorings," the first line consists of a single word standing alone: "Fuggire." ("Escape.")

D'Arezzo's work is characterized by the intense ambivalence and ambiguity of the boundaries between soul and body, freedom and constraint, love and violence. For the translator, the challenge is to maintain the youthful voice of a poet focused on the urgency of music and expression as well as that ineluctable tension—the recurring "si e no" ("yes and no") of the indecisive trees that paralyze her, the sense of being at once "everything and made of nothing" ("tutto e fatta di nulla"). Whether or not d'Arezzo's poems reveal anything about the poet's own experience, they often describe someone (the poetic "I") caught between the expectations of bourgeois Catholic women (even those who are privileged and well-educated) in early twentieth-century Naples and what lies elsewhere—perhaps the dynamic world of avant-garde literature, with Tzara and his Dada compatriots, or perhaps along another path.

As with Dadaism, d'Arezzo flirted with Futurist poetics, but never embraced the movement, likely in part due to one of the central precepts laid out in the Futurist manifesto: the destruction of the poetic "I." As critic Cecilia Bello Minciacchi has noted (in her invaluable collection of Futurist women writers that has served to revive so many voices), d'Arezzo's self-perception at the emotional and psychological level seems to proceed from the physical, sensory level; the inner conflict that infuses her work plays out in the physical world. And while many of the best-known Futurist poems focused on machines, and particularly the revolutionary airplane, d'Arezzo's "Flight" is organic—the wings are her own, a part of herself, allowing the poetic "I" to soar.

Read d'Arezzo's poems in APS 22 here.

Recent News

Writing Fellows

We're pleased to announce the 2024 A Public Space Writing Fellows.

July 1, 2024