News

Monday Memo

November 17, 2019

What we’re talking about this week:

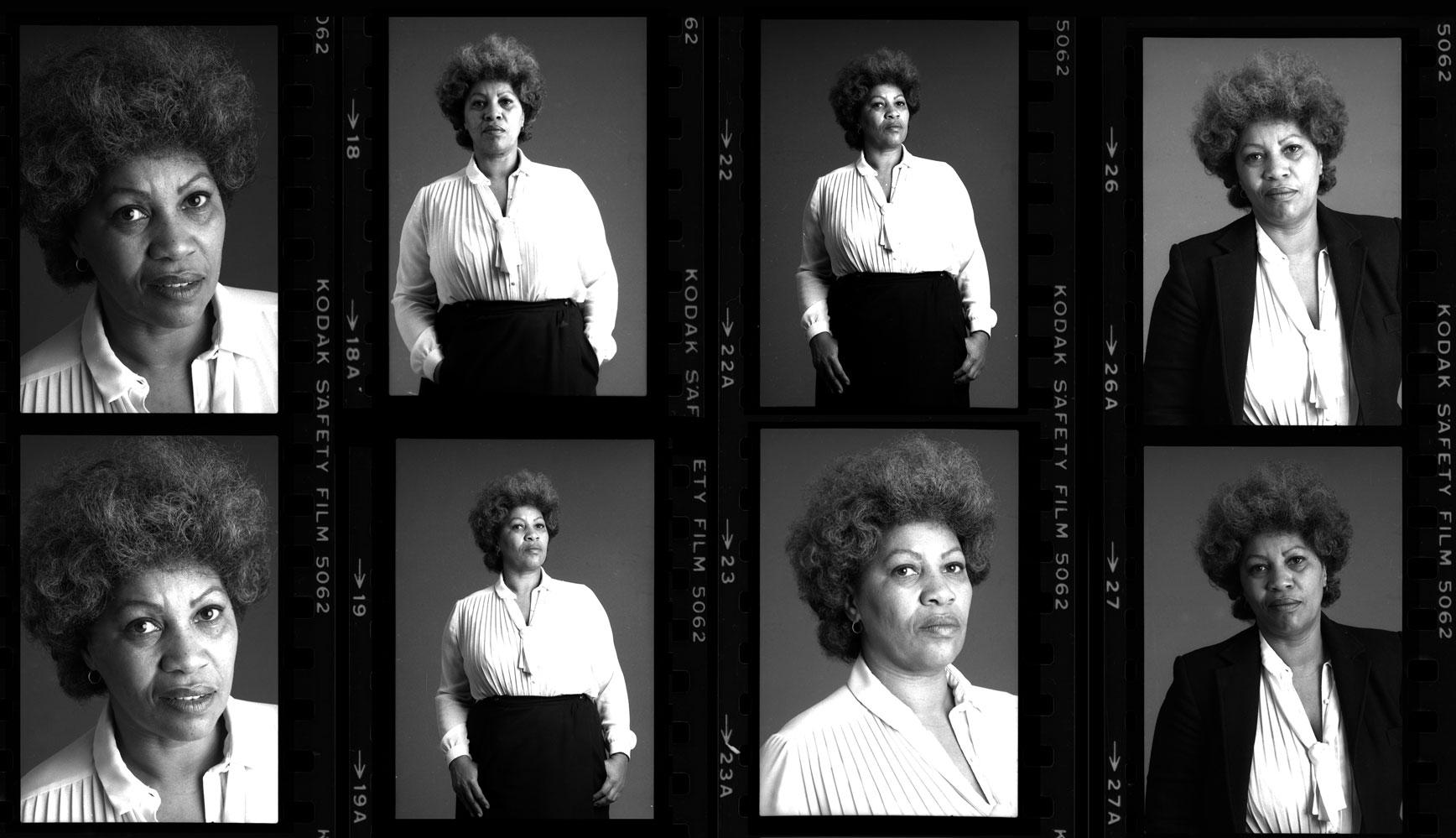

- Toni Morrison’s editorial legacy, as the author’s public memorial at St. John the Divine approaches. Lately we have been thinking about the editors we look to as examples, and Morrison, who worked for years at Random House, is one who often comes to mind. As a senior editor in the fiction department, Morrison received frequent letters from young writers looking for guidance. Though she was surely busy with her own writing and scholarship, Morrison took the time to respond with notes of advice and encouragement. In 1978, the novelist Mary Monroe was 27 years old and just starting out. “I don’t know how it was with you but my family thinks that I am crazy because I want to be more than just a wife and a mother like my sisters before me,” Monroe writes to Morrison. “I can’t tell you how it hurts to receive so many rejections slips and hear so many relatives snickering behind my back.”

“If being a writer is important to you, then you will probably always have to put up with being misunderstood by other people,” Morrison replies. “My only real suggestion to you is to concentrate on writing about things that are most familiar to you....Write the kind of book you would like yourself to read.” We think of Morrison’s generosity often, and have enjoyed reading her correspondences, which are housed in the Rare Books and Special Collections at Princeton’s Firestone Library. We are reminded, too, of Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, the wonderful documentary on Morrison from Timothy Greenfield-Sanders. - Another editor in our pantheon, Deborah Treisman, whom we will be honoring at our annual gala on December 9 in New York. Before Treisman took over the fiction department at the New Yorker, she was an editor at Grand Street and the Threepenny Review, and also translated French poetry and theory. “Someone once told me a story about a government-created computer program for translating from English to Russian and Russian to English,” she wrote in a symposium on translation. “When the developers believed that they had perfected the program, they decided to test it by plugging in a simple sentence: ‘The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.’ The computer translated the phrase into Russian and then translated the Russian phrase back into English. The result: ‘The liquor is good, but the meat is rotten.’” The story, Treisman writes, speaks to the “multiplicity and layering of meaning in seemingly unambiguous words.” It is a cautionary tale for the translator, and one we have been mulling over, especially as we read Stefania Heim’s translation of Giorgio de Chirico’s Italian poems, which are intricate and alchemical, and densely layered.

- And speaking of Giorgio de Chirico, we were intrigued by a recent technical study on the painter’s work initiated by researchers at The Menil Collection. De Chirico made his best-known paintings between 1909 and 1919, but revisited his metaphysical subjects in the 1950s. Sometimes he backdated his later paintings to the earlier period, which poses a challenge to historians. Researchers hope to find new methods for distinguishing the two periods of work, and have identified a pigment the “may prove critical” to the process. It makes us think of the similar scrutiny the translator must apply to language—submitting words to chemical analysis, x-rays, and other advanced methods of poking and prodding. Heim describes the puzzles of de Chirico's poetry manuscripts in her introduction to Geometry of Shadows: “Their tricky dating and paper trails, their self-references, their edits and shifts, their self-quotation and repetition.” De Chirico, she writes, was a “painter obsessed with materials” who “wrote tracts on how to prepare a properly viscous canvas binder," and who "manipulates language too, with palpable attention to technical properties and textures.”

- Jessica Francis Kane’s novel Rules for Visiting, which was included on Oprah’s Best Books of 2019 list. We recently revisited Kane’s Lit Hub essay on the problem of too much metaphor, which includes a charming description of a young writer's ambition: “I am standing at the threshold of the garage and driveway, the exact spot where I first tried to be a writer years ago by pulling a chair and a card table out to write on summer mornings before my grandmother and parents were awake.” It makes us wonder what unseen forces compel a writer to drag out the card table, so to speak, and pick up the pen—and what responsibility the editor holds to cultivate such desire, to elicit it.

- Bette Howland, whose friend Saul Bellow once told her: “As for writing (your writing) I think you ought to write, in bed, and make use of your unhappiness. I do it. Many do. One should cook and eat one’s misery. Chain it like a dog. Harness it like Niagara Falls to generate light and supply voltage for electric chairs.” We are thrilled that Howland’s Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage is included on Kirkus’s Best Fiction of 2019 list.

Excerpts of Toni Morrison's correspondence with Mary Monroe from Miscellaneous Correspondence; Toni Morrison Papers, C1491, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Recent News

Writing Fellows

We're pleased to announce the 2024 A Public Space Writing Fellows.

July 1, 2024