News

The 2022 Bette Howland Prize

September 6, 2022 by Charlotte Slivka

We are pleased to share Charlotte Slivka's essay "March 12," which was selected by Deborah Levy for the 2022 Bette Howland Nonfiction Prize. The prize was established by the author Honor Moore and is awarded annually to a graduating New School MFA nonfiction writer.

Honor Moore is most recently the editor (with Alix Kates Shulman) of Women’s Liberation: Feminist Writings That Inspired a Revolution & Still Can. Moore also wrote about her friendship with Bette Howland in the afterword to Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage: The Selected Stories of Bette Howland.

Judge's Citation:

In this meditation on the death of a brother, Charlotte Slivka attempts to unravel the complexities of addiction from a number of points of view: sister, mother, father, grandmother, society. Slivka is exploring the literary forms an author might employ to gather more insight and offer us a new view. To learn the language of addiction, the author contends, is to understand the complicated back-story of kinship, the ways in which the sick are seen as societally unsightly, and the impulse within us all to seek freedom from the every day anxiety of living. Slivka asks challenging questions and is finding a voice in long-form prose to dig deeper for her readers.

Deborah Levy is a British author and playwright whose most recent works include the novel The Man Who Saw Everything; the story collection Black Vodka; and the autobiography Real Estate (all Bloomsbury).

March 12

Well, here it is, the day all the other days hinge on. After forty years, we still don't know what to do on this day. I still don't know what to do because it's complicated: I still don't want you to be dead and you're still dead all the same; how is this a celebration? I think if you were still hanging around, you'd appreciate the paradox. You’d come up with some very funny, dark, smart, and utterly bizarre thing to say about it; I'm not even going to pretend to know what that is.

Perhaps I should take a poll among your still living friends: What would Marc have to say about being dead on this day? Again! I'm clumsy and your friends are getting annoyed. Thanks to the internet, I reach out to them from out of the blue as if it were Valentine’s Day. But this is what hinges me to you. And I am as aware today as I was on March 13, that time circles around this puncture wound of you. I move out in spirals only to orbit.

We could never get the timing right on March 11. The numbers spilling off into the next moment never finding rest, just kept spilling and spilling, pushing you on to the twelfth.

What really happened that night? The pizza story never really sat right with me. You snored so loud Steve went to get pizza? If that is the truth, then Steve is the dimmest piece of shit that's probably still living.

Does it even matter?

I can't quite put your death in with the other terribly tragic deaths of the young; those young ones who weren't looking or even flirting (as if death were sexy) with death. You knew the risks you were taking and took them. It wasn't exactly a suicide either, but you did spin the chamber and play. Me, witness to your face: stony, angry, lips white with frustration. Mom would say you were suicidal. She wrote a whole bunch about that, wrapping it up with some statistics from 1987. I wouldn't say it that way, too neat: leaves out all the nuance. I would say you were kicking the can to see how far it would go. You didn't mean to die that day. But in your case the days tended toward accumulation to discriminate against you because of the other days. The other days that landed you in the hospital. They build a case regarding what you meant to do that day.

And if there is a tragic portion of this beyond the fact that you were suffering, beyond the fact that you needed help no one knew how to give you, it is this: at twenty-one you had come out of the woods of your dangerous behaviors. You had found recovery and sobriety; you had become a clean slate. I had begun to breathe. You were making plans.

What triggered you to start drinking again? I can only guess and speculate. The world didn't understand addiction in the seventies the way it does now. Our own parents didn't understand when you were offered "just one glass" of champagne at New Year’s. You, still so vulnerable, still growing skin. I think we all thought that your addiction was like a cold to get over. We didn't understand the lifelong journey, impossible to comprehend; the bug lying dormant inside of you because then, we would all have to start looking at ourselves, and we were just fine. Ready to move on into 1982 already. You so isolated, expected to stay clean quietly on your own, no recovery community for you.

Blah. The tragedy is that on March 12 you didn't mean to die that day and that it was stupidity more than Dope that killed you; an accident, compared to some of the other overtly dangerous shit you did. You fell asleep sitting upright in your chair. Being comatose from your stupid cocktail didn't help of course, but if someone had just laid you on your side for example, instead of going out for pizza when your snoring got too loud…

It was like you had signed up for something and your number came up. Doesn't matter how you got taken out.

To name you is something my hoarder heart avoids. It's easier to keep on keeping.

How do we start? You were a baby before you were a boy. Our mother loved you and our father lit cigars over you and was very proud. Nothing was out of the ordinary about this beginning. It was only after settling into the folds of other people's habits that the trouble began.

And you made our grandma smile, something that was extremely difficult to do. Grim-faced Grandma who dressed like the old country in her long dark skirt and gray crochet cap, the pockets of her men's black cardigan sweater puffed by white clouds of tissues. When the sticks in the arms of the white wicker rocking chair in which she always sat had become brittle and broke into holes, and when the holes became nesting grounds for curious little fingers, she crocheted a repair with twine that sunk into the damage like a rope bridge across a wide jungle canyon. She was handy our grandma.

And hadn't she seen her share of death? Even before coming to America from Slovakia, she watched her seven siblings die of some fever. Then her husband, our grandpa gone in his sleep according to Mom when she was fourteen. I used to think that our grandpa had made a deer path from sleep to death for you. Later from Aunt Selma, I found out Mom’s version of that death was a fable created for the tender hearts of children; that the fable had been allowed to myth into my adulthood past the expiration date for such fictions. I suspect now it was a fable for her own heart as well. Mom used to say that she had a gift for grief. Selma said that it was Grandpa's heart after all; that Uncle Bob at ten years old had ridden in the ambulance with him. A scream of sirens shatters the dream, and the truth is loosed and scattered, up for grabs. Whose truth is this? I ask. Anybody's?

Into Sleep

We don’t know how we’ll never know,

the explanation left vague for the children

the truth stranded: his clock wound down,

it was his time, just never woke up. Just never wokeup I was the most curious about. Where do you go when

you don’t wake up? (Years later, high on heroine as I closed

my eyes for sleep, I wondered if I would wake up. This was just

before you who went to sleep high on heroine did notwake up) A fact that was perhaps lost

on everyone at the time: If death

is a deer path, did you follow

your grandpa into sleep?

Selma said Grandma used to be very grand at parties. Said she held court with a long cigarette holder like a 1930s Hollywood film siren. I remember when Mom showed me a very long cigarette holder in a box with other mysterious things she wouldn't let me touch. We didn't know that Grandma. The one we met looked the same way until she died when you were thirteen and I was ten. Already buried when I got home from camp, I was told she died in her sleep. What did you know? When Mom was taken off life support and given morphine, she drifted out in sleep. Pop too in hospice, woke up one morning pissed off with waiting and went back to sleep.

From the pictures I can see you are having a very good time being a little boy; exuberant would be a good way to describe you. It's hard for me to look at those pictures of you before I came on the scene because you look so happy, every picture a celebration. One where it is just you, Mom, and Grandma sitting on the front porch of a gray-shingled Long Island summer home, all of you smiling so broadly, even Grandma; our mother glowing and radiant as I'd never seen her, laughing, unabashedly showing off the gap between her front teeth in lights. Our father must have done something hilarious to get that shot, everybody was having such a good time that day. It doesn't seem right that you should be happier before me, but there it is in black and white.

Whose idea was it to bring this monkey onto the scene anyway? Mom said you used to ask if I could be kept in the garbage pail with the potato skins and banana peels.

My memories are hazy but from what I recall in the early years, it was all about me chasing you and you ditching me. You had all the power, so I only ever thought about my experience of you and how you affected me, and less, maybe not at all, about how I have affected you.

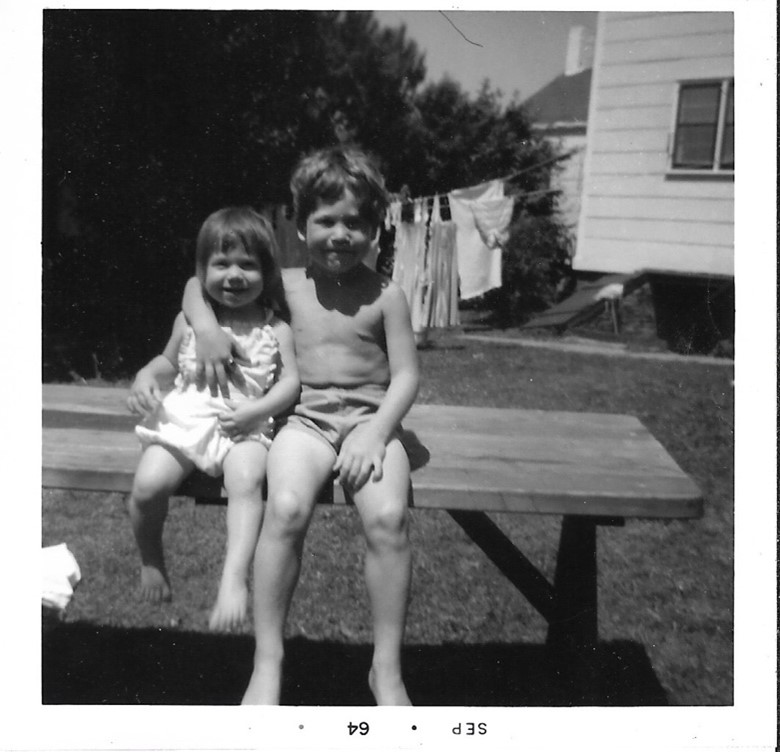

But here again in black and white just after my first birthday:

A picture I dug up out of our father’s things. Dug up as if the picture and its memory were bones in the graveyard of our father's files. I'd never seen it before because I was six when he left and did not have access to his things like we did with our mother’s (I, a menace, tore through the tombs for the find and you...well you), but you were nine, I wonder what you saw. Now all the things are mine: yours, Mom's, Pop’s have all come to me. In an effort to keep you all: I don't look at any of it.

So, it was a surprise to see this picture like the prize in the Cracker Jack box I got because I was looking for something else. It's a picture of you and me and it perfectly matches my memory of what it was to be happy: a picture of a feeling, joyful and unencumbered. I am a year and some change to your four and half, big brother and little sister sitting on the edge of a picnic table. You have your arm slung around me. A diagonal forearm brace across my chest, your hand plopped in the middle of my stomach. You are clearly keeping me from falling off the table which I surely would have as I appear to be swinging the baby legs that have recently learned to do so many things.

I have this little open-mouthed smile and maybe I’m laughing, having fun with my older brother. I lived for it. Because off camera you were such a jerk: torturing me and running away, a game that never seemed to get old. But I stuck out moments like those, crying and running after you, for moments like these in the picture. You made me tough and tenacious. A tenacity that came back to haunt you as I was tied to you like a tether ball.

You have a close-mouth grin with a rumpled chin as if you were proud to be the older brother, protector of this creature that belongs to you. This is the beginning of our arrangement, our understanding that you made all the rules and how you came to be my natural habitat.

The sun is shining, and we are in the country, and we look like two kids enjoying life with none of the burden that will creep in later after the fighting begins. Maybe it's already started, and I haven't noticed yet. Did you? What did four-and-a-half-year-old you notice? In five more years, our father will leave, and our mother will be caught in a cycle of rage that never really ended.

This was the summer between The Bank Street School expulsion and PS 41 taking you on. Who expels a four-year-old? I'm still looking through Mom's records to see what happened. Grace Church will also ask you to leave. Your progress report from when you were seven has you absent for thirty-eight days, and tardy for seven. You're failing across the board except for French and music, and in the section for comments is the work of someone who must be experiencing a rash from a slow but continuous irritation.

He does not do any work, neither in class nor at home. He has only completed one homework assignment since September. This was done the day after I had a conference with his mother in October. There has been no cooperation from his mother only promises. Gets insolent when reminded to do work and not interrupt classmates.

For conduct you get a C-.

You are described as a difficult boy, but still, you make it to third grade even though the commentator for this progress report does not recommend you. In third grade you are absent only thirteen days and tardy for zero. It's all As and Bs except now you're failing French. Even though your grades improve something happens. In Mom’s diaries it is alleged that you stuffed up the toilets and presented your infamous Bullshitting Machine as a class project. Mom was so proud of you for that. Her favorite part of that story is you offering up the word manure in place of shit when the teacher objected. This, of course, is not in the progress report.

So much turmoil to come, but for this moment we are fine and unharmed; enchanted by all the joys in life and all the simple pleasures. I'm tempted to believe in that we broadly.

This picture of us is just a moment, but it's a feeling that seems to have been bottled in my cells. I remember so acutely the sunshine and the pureness of being without shame.

Your love was a mix of ownership and protection, pride mixed with surprise like a slow-moving creature that had wandered into the encampment. The surprise of me, not like you at all; not like anything in the known world that was yours. I followed you everywhere, barely verbal, like a shining thing in motion.

It's very likely our father is taking the picture and is telling you to hold onto me. Are you rumpling your chin because you're being yelled at and told to smile? Is this a picture of early hurt pride? I am oblivious and I'm trying to test the edges of my world: How strong will this arm hold? Maybe I’m leaning into it. The harder its commitment the more embraced I feel. So, I lean.

It's tough for you. I'm pushing and testing and maybe you're being told to inhabit a role you don't understand: the man, the protector, older, wiser. Once you were free to explore and with this new baby sister comes this new thing: responsibility, which you never asked for but yet here it is, and you don't hardly understand it at all. Maybe you're doing the best you can. From the camera view, your best looks a little painful but can pass as pride.

Let’s not forget your protection was a kind of morse code too: There were gaps. Sometimes, in the company with your friends, you tied me up for entertainment, and sometimes when you were supposed to be watching me, you ditched me and left me to find my own harm. You never asked to be the babysitter. You just wanted to run and be a boy unencumbered by this sister thing. I don't blame you. But when the boys you left me with tied me up and left me in the middle of the road without my clothes, I learned a few new things about protecting myself.

Interesting how our father took this picture with him out of the stacks of all the other pictures. I'm thinking this happiness is how he wanted to remember us. It's a time capsule of happiness.

As far as I can tell, everything is chemical, and everyone is an addict. In America, we have an addiction problem. Typically, in this country, we blame the victim for their demise as they are ultimately a liability to someone.

Mind and body in a codependent relationship; mind, and body addicted to each other; it's a perfect circle of supply and demand; a machine that runs so smoothly one hardly notices it running at all until the supply chain gets interrupted. When supply and demand are no longer within the body's control, the body and mind are held hostage, annexed by outside sources which have become dominant by virtue of autonomy.

The body makes its demands to the mind. "Release the fucking chemical! Do what you have to do, or I will torture you until I get it!" The voice of need is so loud. Not all of us are hearing these voices. The body speaks, and the mind translates the language of need into action. Some things are lost in translation. Some things are reinterpreted and mistranslated especially when one’s chemistry is off.

Then there are the mind’s needs; its command to the body to do things; actions that will induce the emotional response needed to trigger the chemical release. Need vs. addiction: is there a line? Where is it?

We, the average of the United States of America, are so quick to judge others and demonize drug addicts, throwing gasoline on the fire. The unsightly ill are moved away from the eyes of those who have been taught to consume fictions of wellness. Our binary world of us and them, haves and have-nots. I think when it comes to addiction it’s just not that simple. As bodies move from one health event to the next, whole tracks of betweenness occurs.

Why is it that some people have a propensity for serious addiction while others don't?

I'm addicted to safety; I'll do anything to stay safe. My aversion to fear is linked to being uncomfortable socially. Anxious. That means, I act out versions of myself when encountered with stark realness. Stripped of pretense and illusion, realness threatens my version of self and feeling safe. A self-fulfilling prophecy of terror. No doubt my social anxiety is an aftershock of this core fear.

How is it that my brother Marc and I born of the same blood and cells, grown up in the same household, could be so different when it came to having a propensity for addiction? I display addictive behavior, but he was full-on addicted. His temperament extreme, mine cautious; his levels of discomfort palpable, his vexations easy; I always sought higher ground. Is it our personalities that dictate who will become addicted and who won't? Our social lives? We were both doing drugs. Okay, he gave them to me. But it was quite likely I would have done them anyway given the time—the 1970s—and the place—Greenwich Village.

I wanted to be just like the kids in the Coca Cola commercials who sang from a green hill about teaching the world to sing in perfect harmony. At six years old, those were my people. I adored the cool hippie girls and wanted to be just like them singing with the chorus of beautiful young people of all nations. An energy exuded from that TV commercial that felt like the beauty of life and filled me with such a longing to be there inside the box with them, that I ran and sat in front of it as close as I could get every time it came on.

Then came the preteen longing to be older. Skirting the edges of Washington Square Park, I eyed the kids who looked cool as they sat around in groups smoking, talking, and playing music. They seemed so free, I wanted to be free too. This sense of freedom I understood later as raised consciousness toward the real, the truth; a shining unseen and immeasurable state one could only inhabit through intuition and the truest sense of being. A magic that gave access to something above and beyond the known and what had become a painful, plainly seen reality.

Raised consciousness the goal; to be free, an ambition. And to get there, kids got high and smoked a lot of pot, as plentiful as penny candy. Kids did drugs to fit in and be cool. The higher you could get and handle it, the higher your consciousness was and the cooler you were, and, yes, at twelve and thirteen, it was a competition.

It is perhaps here that I learned my fear and anxiety and my fear of truly letting go and being free. I was so afraid of coming too close to the source of realness because I had folded in my sense of coolness: was I cool enough? I could play at being cool but to be truly cool was terrifying. It was not cool to be terrified.

Years later I would learn that Sadie, my best friend from middle school and I shared the same anxiety, but we didn’t know this about each other at the time, even while we gave each other permission to risk more and more while testing our world. She was the daughter of enlightened mystical people, artists who had very actively experienced in authentic raised consciousness lifestyle; nothing fake about their freedom.

The most interesting people came and went from their loft: poets, musicians, mystics, filmmakers, and people who were magical and mystical in a way not to be known but only sensed; people who lived in the liminal spaces between the creative disciplines and who preferred the art of the flow, of life, of energy. Prior to living in the city, my friend had lived her early childhood on a compound in Massachusetts with her parents’ friends and their families. A photographer friend of theirs had documented nomadic hippies from coast-to-coast for his book. In it her family is featured and she herself appears on a few pages as a small girl. There is a series of pictures centered on a watering hole where families and friends would meet and swim au naturelle as my mother would say. In the pictures some are caught in the midst of hilarity, all are beaming at the camera. The nakedness of bodies unimportant, it's the nakedness of self that is. They moved back to the city to their loft which seemed to me like a continuation of the watering hole; the ebb and flow of people gathering and dispersing and gathering again.

Why would she have been anxious? Her family life seemed to me ideal, real in the soul, authentic and beautiful. We discuss it now and decide that the things that enthralled us as children seem to be the things that scared us too. No boundaries perhaps for her, not knowing if she was safe; being allowed to run wild and free but not really wanting to. For me it was the realness that brought people to the brink, to the searing edges of reality that terrified me. I wanted to stand unafraid in the face of cosmic truth as the ultimate expression of enlightenment, but all I could manage was a show of fearlessness as I crouched in my brother's shadow.

Marc was not afraid, not at all. That terrifying truth was exactly where he wanted to be. It was there in the loft that Marc would meet Angus MacLise: poet, musician, magician, and kindred spirit. They recognized each other and followed each other's gaze to the same place: the center of everything.

July 1

T-minus 1 day until my birthday, how reckless of me to have lived so long. It's been a slow turn through this life.

Sadie and I: old ladies now, and survivors. New York was brutal in 1982. It's not dramatic to say it was a city that attacked itself. People who lived here could be attacked for anything, every day could be a potential assault and to live here required constant vigilance. But this is a city that uses everything for art, so that anxiety got absorbed into music and art and film; fierce was done with style. Caught in the sap of culture, the bad old days look good.

Meanwhile the survivors are left blaming themselves still, and the stigma of drug addiction holds onto the collective imagination with a litany of victim shaming: weakness of character, reckless wanderlust, selfish indulgence, a willful turn to shallow desires. To this day I’m still trying to understand the all-consuming fire of addiction, that double whammy crippling of body and mind. Becoming an addict isn't an impulsive decision made in a blind spot; it's a growth through need, the need a bloom through the body.

I used to get very, very sick. My body set to purging the heroin right away. The memory of that illness so strong I could conjure that specific nausea at any time and get sick just thinking about it. Is that what kept me off junk, that I couldn't keep it down?

What was it about Marc that he could slide so perfectly into using? Maybe it's not that there's something wrong with him, but something was wrong with me biologically, something critical was damaged. Or maybe I was not damaged enough to push through the nausea and welcome the escape from pain and anxiety too chronic and constant to bear, anxiety that never shut up.

The crossover line is insidious. It hides itself beneath the sand of your feet just as you're crossing over. One day you're on one side of it, partying with your friends, saying, I'm fine, I know what I'm doing; and the next thing you know you're using because you're dope sick, and you can't quite pinpoint when that happened. Once you're over there's no going back. Legal drugs like oxycodone seem even more insidious to me: somehow engineered without the nausea that tells you to stop. You don't even have that chance to think about the line you might be crossing as you're crossing over.

July 2

Today is my birthday, good morning spirit, thanks for sticking around: how's our journey so far? Honestly, I'm grateful, despite the fear.

July 3

I woke up today thinking about learning Marc like a language. I take so much for granted as his family, but that doesn't mean I really know him, I just know my experience of him. And now it's been so long. Writing about him is like meeting up with Sadie after thirty years and having to relearn each other as the people we have become. At least with Marc he didn't go changing. I have to learn him like a language, yes he's still my brother, yes he still lives on in me. Maybe I need to write about him as a witness: is he more of an artifact now? Saying this is allowing the distance in. This is what I’ve been fighting against all this time by not speaking him in. If I keep him present, it’s a different clock I live and die by. Worlds seen and unseen, all of them living. But my inaction is also a death: a wound that closes, a scar to be speculated.

What would I do if he were here now? Who would I be without his death? Was he always going to die? If he had lived until today, would he have ended up in the program, a life hinged to disability? This is one version of survival.

Keeping Marc in my present is necessary, even though I fully admit to cooking up versions of him for my own need. Relegating him to artifact is the heartbreak of death but a deeper death is the death of memory, a betrayal. I'm accustomed to all kinds of living betrayals but none against my dead. Even though he might only live in my mind I have to stay true to the idea of him, hold onto the thread that led to his possibility.

We the living shape our bodies around the past; shape our lies and fictions around the holes in the fabric and create a narrative we don't even know, can’t see, in negative relief. But here alongside us the whole time like a shadow we stopped paying attention to.

So, when I say you are artifact, brother, I am denying the narrative and therefore denying you and denying me too. There's more to this than I know so I play it hot and cold. I know a cold idea when it has no corresponding feeling in the body. I have no trouble reaching back for the pain.

Mom writes on February 6, 1985:

Believe in the miracle, search for the miracle. Believe that the mission of life is to search for the miracle. The Holy Grail is the story. And every person—each of us has the chance to live a life, a story, a new story, an old story made with a new eye, a new touch, mine, yours, it could all be the same story but a different story because it was my body and your body and they are not the same bodies. Bodily reality.

Reasons to live as a prescription and cure for depression. Reason is not the problem.

She has written a chapbook of poems called, The Book of Marc. Going through her records and writings I have discovered her proposal for a nonfiction book of the same name. We are both writing him, my mother and I. The problem we share in writing him is we both get caught up in our own feelings and end up writing about them instead. It's really hard to write about a loved one without smashing through layers of ourselves first. Exhuming our own experiences, thinking that's where the story is. Like demons to be exorcised before we can get to the story which lies at the creamy center of the lollipop. I can only hope that some of those feelings will reveal a story.

So, I look at her proposal to get some thoughts from her side. Our writings converse, a kind of call and response from both sides of the veil. While she was living, we stayed away from the subject afraid of setting each other on fire, both of us preferring to stew in our own grief privately, confit.

I don't like to be critical of my mother. I love her like a mass too large and dense to comprehend; I love her like a black hole that swallows everything completely.

The proposal echoes with her feelings; she reaches but can't get past them.

"The book will encompass:1. The journal of the writer, his mother, of growing into the death, the process of incorporating her grief into her life, the process of change for the mother, the struggle to turn it into art, the act of recognition for Marc and his twenty-two years. How is a mother who has lost a son regarded? How did it change her relationship with her daughter, his sibling? How did his death impact on his sister and change her life? On his father, the other members of the family, friends."

A book by a mother in grief for mothers in grief. I expected something different. Then I realize her Marc and my Marc are not the same. Then I realize my expectation of her has nothing to do with Marc.

Distance Dream

of flesh and blood

the this of you

screen of you

hybrid this life

half machine

part dream part me

smoke blows into a room

to make shape the dream

the beats speak in of Lily

the beating she speaks,

of lives

apart

for me she’s this machine the heart

pulse ... says

she’s thinking, of something

love you too

be lucky

just need you

to be not

myth myth myth.

Connection drives me today. I'm missing my Lily upstate by only two hours, she might as well be across an ocean. Waiting for the dots on my text message screen to turn into language reminds me of how the dead can take you down with them. How it’s a pull and tug with memory and mythology as we yank them up from the underworld to be here now, with us. Why does this remind me of texting with my daughter?

2. It will describe the life and problems at home and at work of the single working mother supporting two children singlehanded. The writer, who was abandoned by her artist husband, will discuss the issues as it pertained to her life as a working woman and as a working mother. If she had to do it over, would she change? Is it possible to be a good working mother?

3. It will discuss the conflict between her roles as a mother and as a wife of an artist involved in the NYC art world of the last thirty years. It will deal with the environment of the art-world child in New York City, with artist parents, with the special issues of artists and family life.

4. In 1987 it is expected that over 40,000 young adults will do away with themselves, in one way or another. This book will deal with the phenomena of growing suicide among young adults, particularly between ages fifteen and twenty-four. It is, in many quarters, an epidemic. What happens? Although focused on Marc, it will also put him in the context of the young suicide blight of our time. Among the people Marc knew was the sixteen-year-old girl down the block, whose ideal parents and beautiful townhouse home in one of the sweetest neighborhoods of Greenwich Village did not protect her from suicidal despair; and Tommy Z as he was known, the twenty-year-old boy from the suburbs attending Columbia University on scholarship. Marc's journals and writings will be included along with those of other members of the family.

Tommy Z was my good friend. One day, at least five different moves, and maybe fifteen years after his death, I found all my letters from him in one of my mother's file cabinets along with full typewritten transcriptions. They were incredible things; handwritten pages and pages with Dick Tracy-style cartoon drawings depicting the awkwardness of being a young man alone in the city trying to make his way through the world and impress the girl he was writing to. So stylish, he had his suits tailored to an early sixties cut with stove-pipe legs and wore his hair like Dirk Bogarde. He should have had a Lambretta. Too shocked for words I realized there were no words as I backed slowly away from her, my letters and transcriptions in hand while she watched me like a guilty child from her desk. She said, “You were away and you stayed away.” (I had gone to Greece with friends the summer after Marc died, and it's true, I did not want to come home.) “You left me to pack up your things when it was time to move.” I considered this scenario as reason, considered my mother's burden, but then reason stopped at the transcriptions.

As horrified as I was that day, her audacity had gone to such an unexpected level, I had respect.

I avoid Marc's things like the grave. But sometimes I look and find something that comforts me, and I feel a little less alone. Written on an envelope in response to Mom taking his mail:

You leech, I found three of my letters downstairs, you take my things, you spy on me, your lower cortex must be between your liver and your spleen.

Funny. Inspired. He tempered his anger with humor because how boring to be only angry; also, how heartbreaking.

I wish she would have written the book for mothers. Now that I'm a mother, having to imagine the death of a child is unimaginable. I'm not sure grief could possibly get larger, go deeper. What I imagine is this: a rip and rend that tears the body through the solar plexus to the spirit; flesh hangs in tatters around a hole where the night pours in. All this and the mother still lives on. Yes, a violence and a violation impossible to measure; like a mass too large and dense to comprehend; a grief like a black hole that swallows everything completely.

I forgive her.

Her grief, outlined while still in the depths of her proposal, never really subsided. It's impossible to write The Book of Marc. And it's unfair of me to judge her for not having enough distance from her feelings. Her grief, like mine, tethers her to him.

Charlotte Slivka was born in New York City and raised in Greenwich Village. She is the recipient of the 2022 Bette Howland Prize in nonfiction judged and selected by Deborah Levy. Her winning essay, "March 12," is an excerpt from a larger work in progress about coming-of-age through music and the NYC underground in the 1970s. Her work has been published in The Brooklyn Rail, Twenty Magazine, Public Seminar, 12th Street, and is forthcoming from Ohm Magazine. She is the current Editor in Chief of LIT, the graduate literary journal produced by alumni and current students in the Creative Writing Program at The New School where she received her MFA in poetry and nonfiction in 2022.

Recent News

Writing Fellows

We're pleased to announce the 2024 A Public Space Writing Fellows.

July 1, 2024