APS TOGETHER

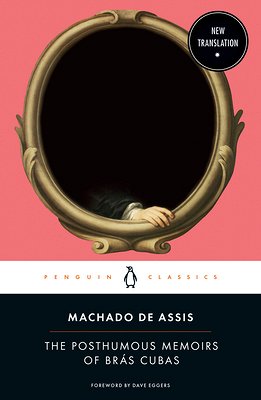

The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas by Machado de Assis

Hosted by Larry Rohter

Began on February 26, 2021

Share this book club

I first stumbled upon The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas early in 1970, during my junior year in college. I had begun dating the woman who would marry me three years later, a linguistics student from Rio de Janeiro, and when I visited her dorm room I would of course leaf through her record collection and library. I already spoke Spanish and she had begun teaching me Portuguese, so when I saw the reference to “posthumous memoirs” in one of the titles on her shelf, I was naturally bewildered and intrigued, and I pulled out the book and began to read.

Initially I was shocked by the narrator’s blasé attitude about death, but soon began to relish the book’s irreverent, picaresque tone. To be honest, many of the specific cultural and historical references went over my head. But a hilariously mordant throwaway sentence like “Marcela loved me for fifteen months and eleven thousand milreis” didn’t need contextualization, and there were many, many moments like that as I plunged my way deeper into the book. I was fascinated, even if I did not fully understand everything I was reading.

When we moved to Rio in 1977, I had another go. We were living in Tijuca, where part of Brás Cubas takes place, and around the city it was still possible to encounter vestiges and remnants of the world in which Machado de Assis lived: buildings, figures of speech, certain Rio types one would meet on the street, landscapes, social customs. All of this enriched my second reading of the book, and increased my admiration for its author. The mixture of trenchant social satire and bold formal experimentation seemed unlike anything I had ever read elsewhere, and by the end I was really hooked, determined to read as much of his work as I could. This guy is kind of a genius, I remember thinking. Why aren't we reading him back home?

Larry Rohter

studied history, political science, and economics at the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service and the Columbia University School of International Affairs. He was Newsweek magazine’s Brazil correspondent from 1977 to 1982 and served as Rio de Janeiro bureau chief of the New York Times from 1998 to 2008. He is the author of three books about Brazil, has written about Brazilian culture and politics for the New York Review of Books, and since January 2020 has been a columnist for the Brazilian weekly newsmagazine Época.

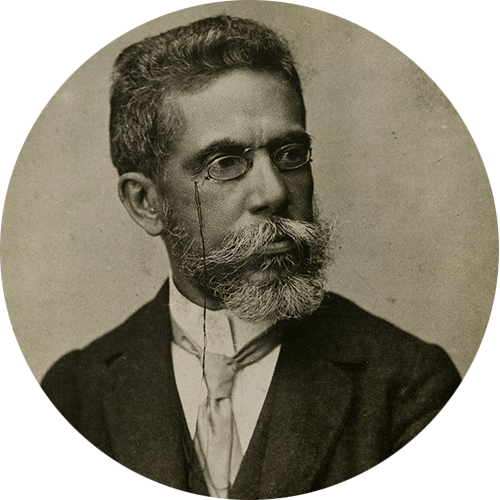

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis

(1839-1908), the mixed-race grandson of freed slaves, was born in Rio de Janeiro. Largely self-taught, he wrote many novels, stories, plays, and poems, eventually becoming the first President of the Brazilian Academy of Letters and gaining recognition as Brazil's greatest writer.

Daily Reading

Day 1

Ch 1-10

March 8, 2021 by Larry Rohter

Right out of the gate, Machado de Assis (or just M) establishes his tone—arch and erudite, leavened with casual cynicism and droll self-mockery. But a playfulness with form is there too: very short chapters offer a hint of the amusing games to come.

Day 2

Ch 11-19

March 9, 2021 by Larry Rohter

M offers a first glimpse of what it was like to live in a society built on slavery in XI. The matter-of-factness with which Brás Cubas (BC) recounts the way he tormented house slaves as a child—one of whom he rides like a horse—augments our disgust.

Day 3

Ch 20-37

March 10, 2021 by Larry Rohter

Poor Eugênia, with her “virginal charm” and “natural grace.” Of all the characters in PM, she may be the only who is wholly sympathetic—and BC treats her badly. Her only defect is physical, whereas all the others are disfigured by their moral failings.

Day 4

Ch 38-58

March 11, 2021 by Larry Rohter

In XLIII, BC’s rival in romance, Lobo Neves, makes his first appearance. “Lobo” means “wolf” in Portuguese, and “Neves” is “snow.” I’ve often wondered whether M was reading the Brothers Grimm while writing PM and decided to insert a very subtle joke.

Day 5

Ch 59-77

March 12, 2021 by Larry Rohter

To me, LXVIII is the single most lacerating and psychologically profound chapter of PM. We see the trauma and suffering of enslavement being transmitted onwards, even after emancipation. And BC’s cynical misinterpretation compounds the tragedy.

Day 6

Ch 78-98

March 13, 2021 by Larry Rohter

This bloc of chapters and the one that follows may be the most overtly political sections of PM, in the sense that M pulls back the curtain on ambition and the maneuverings it inspires, then and now. Is Lobo Neves that much different from today’s pols?

Day 7

Ch 99-122

March 14, 2021 by Larry Rohter

The elite’s obsession with status and the regard of others comes sharply into focus today. Besides chapters on “salutary effects of public opinion,” we have a scene in which Nhã-Loló’s father reveals lower-class origins through his love of cockfights.

Day 8

Ch 123-160

March 15, 2021 by Larry Rohter

M so loved Shakespeare that I can’t help but think he is channeling the funeral oration from Julius Caesar in CXXIII. BC describes his brother-in-law Cotrim as a “ferociously honest character,” then reveals that he smuggles, hunts, and tortures slaves.

A note from Larry Rohter on Machado de Assis

March 15, 2021 by Larry Rohter

Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis is as foundational to Brazilian literature as Mark Twain is to American. The two were contemporaries, grew up in societies disfigured by slavery, and had mordant senses of humor that pervaded their work, but in many other respects, especially as regards style, they were markedly different. Nevertheless, Brazilian literature can be divided into two clearly defined periods: what came before Machado, as he is generally known, and what followed, with all that came after indelibly stamped with his influence. Just as Faulkner called Twain “the father of American literature,” Brazilian writers and critics routinely refer to Machado simply as “The Master” or “The Wizard.”